FSANZ looked at antimicrobial resistant bacteria in the Australian food supply

Read the full report: National surveillance of antimicrobial resistant bacteria in raw retail beef, chicken and pork meat, 2022-23

Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) was funded by the Australian Government Department of Disability, Health and Aging to undertake a project looking at antimicrobial resistant bacteria in the Australian food supply, with the support of all jurisdictions.

Surveillance of raw retail meats was undertaken from September 2022 to July 2023. The analysis was completed in 2024 and the report was released in February 2026. Food samples from three raw retail meats – beef, chicken and pork – were purchased nationally by state and territory regulators. Murdoch University tested all bacteria detected for antimicrobial resistance. Whole Genome Sequencing of selected bacteria was performed to detect genetic antimicrobial resistance determinants.

FSANZ developed a surveillance plan that aligns with the highest international standards. To do this, FSANZ took advice from an Expert Scientific Advisory Group comprising experts from a variety of fields with extensive experience in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and AMR surveillance. FSANZ consulted with all jurisdictions, who participated in the surveillance through the Implementation Subcommittee for Food Regulation Surveillance, Evidence and Analysis Working Group, and agri-food industry partners to understand the management of antimicrobial use (AMU) by industry in Australia.

The objectives for the surveillance plan were to:

- Collect contemporary nationally representative phenotypic resistance data for Salmonella, Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus in prioritised retail meat commodities.

- Collect data to identify the emergence of AMR to high importance rated antimicrobials in these bacteria.

- Undertake Whole Genome Sequence of bacteria displaying AMR phenotypes of interest (e.g. multidrug resistance or resistance to high importance rated antimicrobials) and identify known resistance determinants.

- Ensure data are scientifically robust, reliable, defensible, and comparable to international data and standards.

- Provide a foundational design, according to international best practice, for future ongoing surveillance of resistant bacteria in food providing data that can be compared alongside integrated human, animal, and environmental data collected as part of the Australian One Health approach.

Why did FSANZ look at antimicrobial resistant bacteria in the Australian food supply?

AMR is a serious global issue that needs our urgent action. Australia's response recognises that AMR affects human and animal health, agriculture, food and the environment. The Australian Government has developed a national approach to tackle AMR. Australia's National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy - 2020 and Beyond (the 2020 Strategy) was endorsed by the Council of Australian Governments in March 2020. It sets a 20-year vision to protect the health of humans and animals by controlling and combating AMR while continuing to have effective antimicrobials available. This endorsement recognises that addressing AMR is a matter of national importance.

This holistic and multi-sectoral One Health approach is led by the Australian Centre for Disease Control, jointly with the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry. Other agencies including FSANZ are involved to ensure a whole-of-government approach. FSANZ's two-year surveillance project aligned with Objective 5 of the 2020 Strategy and provided an opportunity to advance the evidence base for AMR in retail food in Australia.

Research about how antimicrobial resistance spreads in Australia is ongoing and new information is continuing to emerge. However, significant gaps remain in Australian data. One of these is data about AMR and the national food supply. Very few nationally representative studies have been undertaken.

Food sits at the interface between humans, animals, and the environment. It is considered an important driver of AMR because it can spread resistant bacteria to humans. Foodborne illness can also be caused by some bacteria, and there are concerns that antibiotic resistant foodborne infections may become more common and increase the risk of severe illness and death, particularly for the most vulnerable in our community.

Continued monitoring of the food supply for resistant bacteria is important for several reasons:

- It can provide information on the prevalence of resistant foodborne pathogens and other medically important bacteria present in the food supply that might be spread to humans.

- If monitoring occurs over a number of years it can help identify trends in AMR and emerging AMR to medically important antibiotics that can inform Australian policy decisions.

- In the future, if monitored as part of an integrated One Health surveillance system, it can be compared to data from humans, animals, and the environment and contribute to a more holistic understanding of how antibiotic resistance spreads and the contribution of antibiotic use, both for humans and animals, to AMR in Australia.

What causes AMR?

AMR occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites change over time and no longer respond to antimicrobials, making infections harder to treat and increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness and death.

Antimicrobials is a term that is used to refer to antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics. Antimicrobials are medicines used to prevent and treat infections caused by microorganisms in humans, animals and plants. Bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics, viruses to antivirals, fungi to antifungals and parasites to antiparasitics.

The main cause of AMR in bacteria is antibiotic use. While antibiotics are essential to modern medicine, the more antibiotics Australians use, the faster resistant bacteria will develop. Because antibiotics in Australia are used to treat humans and animals, to reduce AMR we need to understand the interconnection between people, animals and our shared environment. This is called a 'One Health' approach.

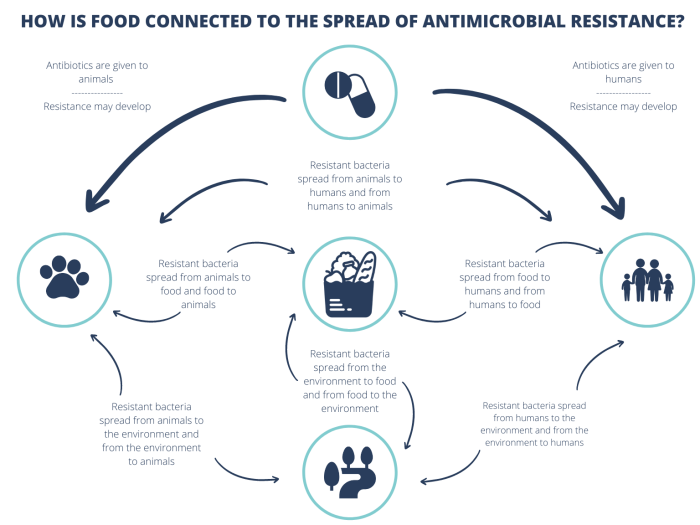

A One Health approach is important because antibiotic resistant bacteria can potentially spread between and within sectors in a number of ways.

Antibiotic use by humans puts pressure on bacteria to become resistant. Resistant bacteria can spread between people via direct contact, coughing, sneezing and exposure to bodily fluids. Bacteria can also pass between companion animals, livestock or wildlife and to humans through direct contact.

Antibiotic use in animals also puts pressure on bacteria to become resistant. Resistant bacteria from food-producing animals can move through the food supply chain and be present in food consumed by humans. Resistant bacteria can move through the environment and contaminate food crops. Humans can transfer resistant bacteria from themselves to food during production or preparation.

Resistant bacteria present in animal waste, human waste and food waste can also contaminate the environment, including soil and water. Bacteria that are present in the environment can then spread back to animals, food and humans. This interconnectedness makes a One Health Approach essential to tackling the problem of AMR.

Why is AMR a problem?

AMR is a serious health threat to both humans and animals because it threatens to reduce the effective prevention and treatment of infections caused by bacteria, parasites, viruses and fungi.

The threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a major concern in the world today. Antibiotics are antimicrobial medicines. They work by killing bacteria, slowing their growth or stopping them from causing infection. Antibiotics help the body's natural immune system fight bacterial infections.

Since the 1940s, antibiotics have saved millions of lives and have contributed to the increased life expectancy today. They also made many lifesaving medical procedures safer including:

- organ transplantations

- chemotherapy

- caesarean sections

- surgeries.

AMR happens when disease causing bacteria become resistant to the antibiotics used to kill them. Taking antibiotics will destroy most of the bad bacteria, however, sometimes a few resistant bacteria can survive. These can then multiply and spread. Bacteria can develop resistance through mutation (random changes to DNA) or sharing of genetic material from one bacteria to another. As a result of AMR, antibiotics can become ineffective and as a result common diseases are becoming untreatable, and lifesaving medical procedures riskier to perform.

Misuse and overuse of antibiotics contribute to the emergence and spread of resistant bacteria. Bacteria are developing resistance to classes of antibiotics faster than new, more effective antibiotics can be produced. Most of the antibiotics used today were developed over 30 years ago and only a small number of new antibiotic classes have been approved in the last two decades. Some bacteria have become resistant to all classes of antibiotics that were effective against them and today there are no longer effective antibiotics to treat the infections they cause.

There are at least 700,000 deaths each year globally from antimicrobial resistant infections. This is projected to increase by 2050 to 10 million annually if no action is taken[1]. It is estimated that an average of 290 persons die each year in Australia due to infections with resistant bacteria[2]. By 2050 the estimated annual impact of AMR on the Australian economy could be between A$142 billion and A$283 billion[3].

More information

For more information on AMR, the Australian Government National Strategy, and what you can do to help reduce AMR please visit https://www.amr.gov.au

[2] https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/stemming-the-superbug-tide_9789264307599-en.html

[3] https://outbreakproject.com.au/2020/04/22/superbugs-to-trigger-our-next-global-financial-crisis/